| Sorted by date | |||

page026from Building IdeasChicago World Exposition. The advancedaerodynamics and rear-wheel steering of the car – ineffective at high speedsdue to its loss of contact with the ground – were directly inspired by the formof an aeroplane fuselage, confirmed by the famous photograph of one of Fuller’slater prototypes of the car, parked on a runway next to his own equally curious-lookingaircraft, the amphibious Republic Seabee.5 A telling example of Fuller’s romanticdesire to make use of all the most advanced technological possibilities – evenwhere they are not necessarily required or particularly appropriate – comes inhis summary of the goals of the Dymaxion project, made in 1983, the year of hisdeath: SinceI was intent on developing a high-technology dwelling machine that could beair-delivered to any remote, beautiful country site where there might be noroadways or landing fields for airplanes, I decided to try to develop anomni-medium transport vehicle to function in the sky, on negotiable terrain, oron water – to be securely landable anywhere like an eagle.6 Itis here that Fuller’s debt to those first great machine-age poets andromantics, the Italian Futurists, becomes apparent, in his echoing of theinfatuation they experienced when confronted with new technological possibilities.As the 1914 manifesto of the group makes clear while also betraying the provenanceof some more recent high-tech preoccupations: Wemust invent and rebuild the Futurist city: it must be like an immense,tumultuous, likely, noble work site, dynamic in all its parts; and the Futuristhouse must be like an enormous machine. The lifts must not hide like lonelyworms in the stair wells; the stairs, become useless, must be done away withand the lifts must climb like serpents of iron and glass up the housefronts.7

5 Reproduced in Martin Pawley, BuckminsterFuller, Trefoil Publications, London, 1990, p 81. 6 R. Buckminster Fuller, quoted in Martin Pawley,Buckminster Fuller, Trefoil Publications, London, 1990, p 57. 7 Sant Elia/Marinetti, “FuturistArchitecture”, in Ulrich Conrads(ed.), Programmes and Manifestoes on 20thCentury Architecture, Lund Humphries, London, 1970, p36.

|

|||

|

|||

|

|

|||

page025from Building Ideasacknowledged by most architectural criticsas a classic example of the New Architecture that modernists strove to achieve.The Dymaxion, however, with its circular drum of living space suspended from acentral Duralumin mast housing all the mechanical services was, to Banham, thetrue realization of Le Corbusier’s notion of the “mass-production house”. Itwas, for him, a pioneering example of the kind of pure “technology transfer” aswell as the “served and servant spaces” arrangement that were to become basicprinciples of the developing high-tech tradition. Like the later geodesic domeprojects which simplified the form of the Dymaxion house into a keletalsheltering roof structure made of repeated modular components, Fuller’s ideaswere presented as the inevitable outcome of the efficient use of the latest newmaterials. He disparaged the seemingly trivial preoccupations of architectslike Le Corbusier and others who professed to be searching for a rational andfunctional architecture while, to his eyes, merely indulging in irrelevantstylistic manipulations more appropriate to the whims of the fashion industry: “Wehear much of designing from the ‘inside out’ among those who constitute whatremains of the architectural profession – that sometimes jolly, sometimes sanctimonious,occasionally chi-chi, and often pathetic organization of shelter tailors”.4 Withits lightweight, cheap and portable, frame-and-skin construction the DymaxionHouse concept actually grew out of the same obsession with the forms of yachts,ships and early aircraft that had inspired Le Corbusier’s radical thinking,even though this had lead to quite different results. The fact that Fuller wasmore interested in the prototype than its mass-production possibilities isillustrated by his unwillingness to launch into production for the militarymarket after the war, when orders for his Dymaxion-inspired “Wichita” houselooked set to exceed the first 60 000 units the factory was preparing toproduce. Fuller’s hesitancy may partly have been due to the disastrous debut ofhis first Dymaxion car, involved in a fatal accident at the gates of the 1933 4R. Buckminster Fuller, Nine Chains to the Moon, Southern Illinois UniversityPress Carbondale, 1938 & 1963, p 9.

|

|||

|

|||

|

|

|||

page024from Building Ideas

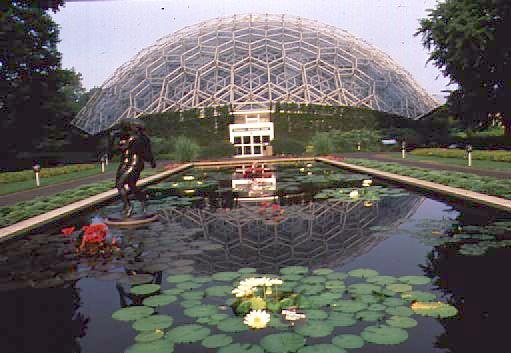

9 Murphy and Mackey – Geodesic Dome, St.Louis “Climatron”, 1960. (Neil Jackson) innovations and the spirit of the pre-wararchitecture – now seen as in need of reassessment. FromBanham’s point of view the “white architecture” of the 1920s and 1930s andfailed to live up to the promise of the great rallying cry of early modernism –Le Corbursier’s famous claim from 1923 that as house is a “machine for livingin”3 – and he saw Fuller, finally, as the herald of a true machine-agearchitecture. In Banham’s best-known book called Theory and Design in the FirstMachine Age (1960) he compared Fuller’s innovations in the Dymaxion Houseproject from the late 1920s to the allegedly “technically obsolete”architecture of Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye – Designed and built around thesame time and 3 Le Corbusier, Towards a New Architecture,translated by Frederick Etchells, Architectural Press, London, 1946, pp12-13.

|

|||

|

|||

|

|

|||

Messagefrom General CriticsHere these pages about the technology and architecture, which present as the influences from techniques by structures more.

|

|||

|

|||

|

|

|||

page023from Building Ideas

Fuller.Probably the only architect to have an atomic particle named after him (“Buckminsterfullerene”,a molecule of carbon which has a similar structure to his “geodesic dome”),Fuller is perhaps best known for the dome he constructed for the 1967Exposition in Montréal,Canada, based on the geodesic principle and still standing today, thoughwithout its original Plexiglass covering. As a tireless innovator of newmaterials and technologies Fuller had become famous for a series ofmass-production prototypes such as the “Dymaxion” series of bathrooms, cars andultimately houses, from the 1920s to the 1940s, which found only limitedpractical application but significant theoretical interest. One of Fuller’sgreat apologists in this period of ferment in the 1950s was the English criticReyner Banham who took up his technological cause and gave it an “academic”respectability. It was largely through Banham’s enthusiastic promotion thatFuller’s ideas of a technology-driven modern architecture fed into the work ofthe Archigram group, although Banham was also concerned to establish a sense ofhistorical continuity between these new technological

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

... ...

... ... ... ...

... ... ... ...

... ... ... ...

... ... ... ...

... ... ... ...

... ... ... ...

... ... ... ...

... ... ... ...

... ... ... ...

... ... ... ...

... ... ... ...

... ... ... ...

... ... ... ...

... ... ... ...

... ...

8 Louis I Kahn – Richards Medical ResearchLaboratories, University of Pennsylvania, 1957-64: Entrance level plan.(Redrawnby the author, after Louis I Kahn)

8 Louis I Kahn – Richards Medical ResearchLaboratories, University of Pennsylvania, 1957-64: Entrance level plan.(Redrawnby the author, after Louis I Kahn)